Monitoring

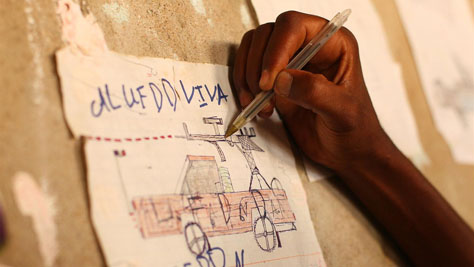

© UNICEF/NYHQ2010-1153/Olivier Asselin

© UNICEF/NYHQ2010-1153/Olivier Asselin

Introduction to monitoring for the MRM

The monitoring of grave violations of child rights is a complex task. Four sections are included in this section: An introduction to monitoring; data collection; verification; and documentation. All information obtained needs to be managed - while part of monitoring, information management is a complex area in its own right and is therefore covered in the next chapter of the manual.

Figure 2: An overview of monitoring and its components.

What is being monitored?

The violations that are monitored are:

- Killing or maiming

- Recruitment or use of children in armed forces and groups

- Attacks on schools or hospitals

- Rape or other forms of sexual violence

- Abduction

- Denial of humanitarian access for children

All six grave violations should be monitored, regardless of which violations have triggered the MRM. For example, if the MRM has been triggered in a country situation where one group has been listed for recruitment and use, this does not imply that the MRM should be limited to recruitment and use; it should undertake monitoring on all six grave violations.

Whose activities are monitored?

All parties to the conflict - whether state armed forces, paramilitaries, or non-state armed groups - should be monitored. Parties to be monitored are not limited to those listed in the annexes of the annual Secretary-General's Report on CAAC. For example, if the MRM has been triggered in a country situation because of the listing of one party, this does not imply that the MRM should be limited to the activities of that party; all parties to conflict in that country situation should be covered.

Should an armed group change its name or fragment into multiple groups, monitoring would continue for new factions as well as the original groups. It should be noted that the monitoring and reporting of an armed group does not provide any form of recognition or legal determination to that group, and this should be communicated to all parties concerned.

Who should be undertaking the monitoring?

Monitoring should be undertaken by personnel from the CTFMR, and by partners, who have been specifically trained in the MRM. All information must be verified as per the standards outlined in the Verification section below.

Roles of different actors in MRM

UN mission and UN agencies

As detailed in the Guidelines and above, the SRSG or the RC co-chair the CTFMR with the UNICEF representative and take the leadership of the MRM. Other UN agencies, such as OHCHR, UNHCR, UNDP, ILO, OCHA, WFP, UNIFEM, UNFPA, UNESCO, etc., will play different roles depending on their presence and mandate in the country.

DPA and DPKO missions are subject to a particular child protection policy that gives added attention and strength to MRM activities in their areas of operations. A key aspect of the policy is the deployment of specialized CPAs among whose main tasks are monitoring and reporting, training, and mainstreaming of child protection in the missions. CPAs often play the key coordinating and drafting role on behalf of the SRSG. Please see Annex VIII [PDF].

NGOs

NGOs, both international and local, can be invited to take part in the CTFMR upon consent of the CTFMR members. NGOs may associate themselves to the work of the CTFMR either as formal members or, in situations where security or other considerations preclude this, they may be associated informally. As with all task force members, NGOs involved in MRM Task Forces either formally or informally should be actively involved in monitoring and reporting activities and able to contribute to the work of the task force.

Additional child protection actors and monitoring networks

The MRM Task Force should also seek to build and support local networks that can contribute to the MRM. Though many of the organizations in child protection networks of the child protection sub-clusters may not actively participate in the MRM due to their mandate, capacity, security concerns and or sensitivity of the issues to be monitored, the networks can contribute to the MRM by:

- alerting Task Force members to violations

- increasing information-sharing through existing thematic groups

- assisting Task Force members to access communities

- being involved in the response component of the MRM

The relationship between the MRM Task Force and the broader networks does not need to be formal, but the MRM Task Force should establish a clear focal point or procedure through which alerts and other assistance can be channelled.

International Committee for the Red Cross (ICRC)

The ICRC is not a formal member of the CTFMR, but it remains a key actor in ensuring respect for international humanitarian law, and as such is a party that should be consulted. The CTFMR may invite the ICRC to attend relevant meetings with observer status, if deemed appropriate.

Government

Security Council Resolution 1612 (2005) [PDF] emphasized the need for the MRM to operate with the "participation of and in cooperation with" national governments.39 However, governments are not part of the CTFMR, as monitoring and reporting is, by definition, an independent and neutral activity. The "participation of and in cooperation with" national governments does not require governments to be involved with monitoring or "consent" to the report. In respect of states, there is a requirement for governments to be engaged with the MRM by facilitating and supporting the collection of information by granting access to conflict-affected areas; allowing contact with non-state armed groups; respecting and ensuring the respect of the protection owed to victims, eye-witnesses and monitors.

Governments hold the key responsibility for children in the country and are therefore the key actor responsible to provide prevention and appropriate responses, and to ensure accountability mechanisms for grave violations against children. The establishment of a parallel forum is encouraged to enable the MRM Task Force chairs to regularly meet with the Government and other parties to discuss violations, Action Plans and response; and to discuss reports, recommendations and Security Council Working Group conclusions. The appointment of focal points in key governmental bodies, and the formation of an inter-ministerial coordination body can increase effectiveness. For example, it could include relevant ministries and institutions such as the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Defence, Children's Welfare, Social Affairs, Human Rights, Interiors, etc. It has also been found helpful if this body is coordinated by a high-level focal point.

Parties to the conflict

Parties to the conflict, including states and non-state armed groups, should not be involved in the monitoring and reporting components of the MRM. They have an important role, however, to play in relation to prevention, response and accountability.

Government departments and agencies, and non-state armed groups may, however, be sources of information for the monitoring and reporting activities, to alert Task Force members to violations that subsequently require independent verification.

Humanitarian clusters

Whilst the MRM Task Force is unique and distinct from the humanitarian clusters operating in the country, the Task Force should work closely with and keep the clusters informed of its work. However, the distinction is an important principle as some of the NGOs involved in clusters may not wish to be associated with the MRM for security reasons. When clusters are developing assessment tools, they may choose to develop definitions that are consistent with those of the MRM, where applicable.

The Task Force should also seek support from the protection cluster and other clusters for programmatic response to grave violations against children's rights, particularly the child protection area of responsibility or sub-cluster and the gender-based violence sub-cluster. Cluster organizations should also refer cases to the MRM as appropriate.

The nature of information collected for the MRM

For the purposes of the MRM and reporting to the Security Council, it is imperative that the information provided is timely, accurate, reliable and objective.

Grave violations against children fall into three groupings:

- Incident involving one child

- Incident involving a number of children

- Impersonal violations (i.e., attack on a school or hospital, and denial of humanitarian access), which may not have physically impacted on a specific child at that point in time. [However, the physical or other impact on these sites or lack of access in the case of humanitarian efforts may later have an impact on children, which is important not to miss.]

For the purposes of the MRM and reporting to the Security Council, it is imperative that information provided is timely, accurate, reliable and objective. Therefore, the core information required and verification standards remain the same, regardless of whether it concerns a large-scale incident such as an attack on a village, an individual violation such as sexual violence, or multiple children such as a group of children abducted (See more under the Verification section below). Note that while the core information required remains the same, it is vital that, in cases of sexual violation, the interview is conducted by specialist trained staff.

For the purposes of monitoring grave violations, it is possible to monitor incidents accurately but to be recorded in MRM reports sent to the Security Council with anonymous information40 and, therefore, provide protection for victims, sources of information and staff from NGOs and UN agencies. (See more details under the Documentation section below).

For the purposes of appropriate accountability and response measures, more detailed information should be held on each child against whom grave violations have been committed. While the child profile is needed by the CTFMR, personal information is not essential to be held on the CTFMR information system, but can remain with the partner organization. This would allow reports to be generated from information held and provides the possibility of referring back to the organization holding the individual information if further clarification is required.

Key messages - Monitoring

- Ensure clarity to all parties and to staff involved in MRM on what is being monitored

- All parties to the conflict are monitored - State armed forces and non-state armed groups

- Personnel undertaking monitoring must be specifically trained in the MRM

- All information must be UN verified. The chair of the CTFMR is responsible for establishing a verification system to ensure that the inputs provided are timely, objective, accurate and reliable. State and non-state parties should not be involved in the monitoring, but can provide an alert to an incident.

Information gathering

Accessing information

Some personnel who are full-time monitors (e.g., human rights officers, and child protection officers) will be in a position to actively seek and collect information, while other staff may not be in this position but may access information during the course of their normal programme activities. This highlights the importance of awareness-raising and training of all partners in the field.

Some of the ways in which information can be accessed or reported are through alerts to CTFMR members. (This information should then be verified as detailed in the Condentiality section under Information Management.)

- Networks and contacts - e.g., a CPA who establishes a network of partners interested in child protection and who is alerted by this network on a regular basis as part of his or her work.

- Special investigations - e.g., an office such as OHCHR that undertakes a special thematic or incident-based investigation and comes across relevant child rights violations.

- Programme providers - e.g., NGOs, civil society or service providers such as hospitals that, in the course of their work, are alerted to child rights violations.

- Trained staff from other disciplines - e.g., trained peacekeepers who provide information on child rights violations in the course of their missions or tasks.

- Non-trained staff from other disciplines who become aware of an incident but do not have the training or specialist background to take a report (e.g., water, sanitation and hygiene officer, DPKO logistics officer or UN driver).

- Victim or witness-driven contact - e.g., victims or families who access field offices of CTFMR members to report or seek assistance.

- Media reports - e.g., a reliable media source highlighting serious allegations of grave violations.

Members of the CTFMR should be conscious of potential biases that may exist in data collection if it depends upon self-reporting by individuals and witnesses to the UN or NGOs, and should actively seek to rectify such potential biases through active inquiries where necessary. For example, where demobilization programmes exist with attractive incentives, child and or caregivers may falsely report their association with an armed group.

Interviewing children and other persons providing information

Below are some general pointers when taking information on sensitive or painful subjects.

- Ensure the best interests of the child: Persons involved in the MRM should uphold the fundamental principle that the best interests of the child are to be protected.

- From the outset, consideration must be paid to the approach depending on the person being interviewed and the situation.

- Speaking to children generally requires different approaches depending on age.

- Girls and women may feel more comfortable speaking to a female interviewer.

- In some cultures, boys may find it difficult to discuss sensitive subjects with a woman.

- Is the information likely to be sensitive or break cultural taboos if discussed?

- What may be the implications for the victims or witnesses if they tell their story? - It is important, where possible, to avoid interviewing victims and witnesses repetitively regarding the same violation. One of the first questions a field worker should ask is if the person has already provided information to another organization. If this is the case, the field worker should consider contacting the relevant organization to see if it has sufficient verified information on the case.

- Children and their caregivers providing information should be informed of the purpose of the interview. From the outset, the field worker must ensure that the child, parents, family and community understand what they will (and will not) get out of their participation in the data collection process and whether there could be any other potential implications from their participation. It should also be clearly explained, at the time a statement is provided, that the information collected does not necessarily intend to secure criminal prosecutions, and that these are steps that the information provider can separately do through appropriate channels.41 The field worker should not indicate or promise that the MRM will improve the participant's individual situation.

- Once information has been provided, ask if consent is provided to share information for the purpose of monitoring. Explain what information would be shared and what would not. Ask this at the start or end of the interview as appropriate to the situation.

- Informed consent for advocacy may also be desirable. Where appropriate, consent of the child and/or his/her guardian may be required in order to engage with local, regional, national or international actors (e.g., communication with human rights mechanisms) on responsive action related to the case. Informed consent can be given by signature on a consent form, if appropriate, or orally, after which the field worker would note that consent was given. If deemed appropriate in the given setting, a consent form could be made available in the local language and should be read to those who are illiterate. Written consent is recommended where individual advocacy is being undertaken.

- Information on sensitive subjects is normally easier for victims or witnesses to share if they are allowed to tell their own story, at their own pace, rather than in the format of an interview. Also, children may not have the words to describe sexual assaults - listen carefully and do not expect specific words or descriptions that an adult may use.

- Rephrase and read back the information provided to ensure it is understood correctly.

- Ask questions to clarify.

- It can be off-putting for people if an official-looking document is used while they are being interviewed, and it may be preferable for the staff member to complete the document later from notes.

- On the contrary, some persons actually like to see that their story is being taken seriously and documented.

- Finding a quiet space can be challenging in small villages where everyone crowding around is the norm; if information is provided in this manner, people must be informed that it is impossible to ensure confidentiality when stories are told with an audience.

- Be aware that a child may have suffered multiple violations and may not disclose the more sensitive of these initially. Listen carefully for clues about this.

Security when collecting information

Security is of great importance and must be a prime consideration when collecting information of grave violations against children.

Who is at risk?

- Children and their families - the children who have suffered the violations and their immediate families, whether they have reported the incidents themselves or the information has come to the MRM via a third party.

- Witnesses and other information providers - any individual who reports an incident or who provides information about one, whether first-hand or as a third party, or anyone who provides access to relevant documentary evidence.

- Monitoring staff - both the staff who take reports on incidents AND those who are responsible for storing and analysing the data involved can also be vulnerable. It should be stressed that local staff working for NGOs and/or at the UN are typically more vulnerable and due consideration should be given to their protection.

Minimizing risk when collecting information

- A general risk assessment should be carried out in areas of operation prior to undertaking monitoring activities in conflict areas. This may be a UN security assessment; specific organization assessment or the assessment by the individual staff member on the day. Staff should be continually aware of the risk level in all situations and make decisions on information gathering accordingly.

- When asking children specific questions or information relating to the activities of the armed force or armed group, great care should be taken to ensure the child's safety and confidentiality. When a child or a witness wishes to tell you details, allow them to speak at their own pace and what they feel comfortable to do so.

- For the security of the individual staff member, the organization, children and individual witnesses, the section on confidentiality must be adhered to, and persons advised on this (see the Confidentiality section under Information Management).

- To ensure security, staff should be advised that information received on grave violations of children's rights should only be discussed with others on an essential need-to-know basis.

Key messages - Information gathering

- Staff should continually be aware of the situation and risk levels for both themselves and persons being interviewed.

- If at any time a staff member becomes concerned regarding immediate security for himself/herself, the victim or the witness, the interview should be halted.

Verification

Basics of verification for MRM

The UN Secretary-General and the heads of the UN country presence [SRSGs/RCs] are responsible and accountable for the veracity and accuracy of the information provided in the reports and, as such, the information must reach the standards of verification used within the UN system. Hence, the CTFMR must have a verification system and the chair of the CTFMR must be satisfied that the inputs reach the minimum standards of verification outlined below, and endorse the reports.

Information in the reports generated under the MRM identifies individuals and parties to the conflict as perpetrators of grave violations against children. This information has potentially serious political and other implications. It is therefore important that the information is verified to the highest standards.

Verification includes three general considerations:

- Identifying and weighing the source of the information - Is it a primary source (an eyewitness) or a secondary source, someone who is aware of the general circumstances prevailing or has non-eyewitness information pertaining to the case in question (see Figure 3 below). Primary sources are always more reliable than secondary sources.

- Triangulation or cross-checking of information concerning the case in question. For example, this includes testimony from various independent sources (primary or secondary) regarding the incident in question so that the MRM staff member is able to reasonably assess the veracity of the allegations.

- Analysis of the veracity of the allegations through application of the MRM staff members' reasonable sound judgement in light of additional information provided by other specialists (e.g., security specialists, peacekeeping staff, and relevant political and human rights experts).

- The information has to ultimately be endorsed by the co-chairs of the CTFMR.

| Primary sources | Supporting sources | |

| Testimony | Material | |

|

Testimony from:

|

|

|

Figure 3 - Primary and supporting sources of information

Minimum standard of verification

Multiple sources of information are ideal.

If you have information from only one primary source, the following criteria should be met:

- Information has been received from a primary source. A primary source is a testimony from the victim, perpetrator or direct eyewitness.

AND - The information has been deemed credible by a trained and reliable monitor.

AND - The information has been verified as such by designated person(s) of the CTFMR.

In some situations, supporting sources such as police and medical reports or official government documentation of an incident (especially in sexual violence), if assessed as credible by the CTFMR, may be sufficient. In the best interests of the child, such an official document maybe taken in lieu of an interview with the primary source.

Information that does not meet the full criteria for verification

When the CTFMR has information that has been assessed credible, but for which complete verification has not been completed or is not possible, this should still be documented and may be reported as 'alleged' or 'subject to verification'.

Collecting information through testimony42

The field worker should in each instance ask the victim or witness to explain what happened from start to finish. The following provides guidance on minimum key aspects to be documented and which will aid verification:

- Violation(s) - What violation(s) were committed?

- Circumstances and details of the violation.

- Location: Be as specific as possible. Ask the person to draw a map of the village if it will support the process.

- Date and time of day: Depending on when it happened, this can sometimes be difficult. Field workers should be aware of any calendars unique to ethnic groups in the area.

- Identity of the victim: Attain the information on the name, age, sex and number of children affected by the incident, if relevant. Other information relating to specific vulnerabilities and status of the individual/group may be useful: ethnicity, religion, internally displaced person, refugee, unaccompanied minor, separated child, etc.

- It may be necessary to ask further questions to determine the age of a child, particularly when in adolescence.

For date of birth, the parent or carer may only know the year; if there is any doubt about the year of birth, then check the year by asking relevant questions, such as: (NOTE: These sample questions are only for situations where the interviewer is unsure of the age.)- Age of other siblings and ages. Determine age differences.

- Any significant event that occurred during the year of his/her birth (or before or after)

- Whether he/she had been to school? - How long ago did he/she finish primary school? (secondary, if appropriate)

- Has the child met different age-appropriate cultural signposts/events?

- How tall is he/she?

- Point out another child who looks the same age.

- Alleged perpetrator(s): Try to identify the armed group/force. Some people will be able to identify the perpetrator by recognizing the uniform. Be sure to ask if the perpetrator was wearing a uniform and, if not, how the respondent was able to identify his group membership. Be aware that in some situations fighters from one group will wear the uniform of another to try to place blame on an enemy or sow confusion within a population. Ask the respondent if they know which brigade or battalion the perpetrator is from (be aware of how the armed forces or groups in your areas are organized and the numbers or names of their divisions). See also if the person is able to identify an individual perpetrator by name or rank (e.g., you can ask the respondent whether the perpetrator had any stripes or other markings on his uniform). At a minimum, it is sufficient for the perpetrator to be identified to the level of armed group/force, although for advocacy and accountability purposes further details would be needed.

- How and why the armed group/force committed this violation: Although this may be speculation, it could provide useful information that the field worker may verify later.

- Details of others who may have witnessed it that could provide additional information and aid verification.

- How does the person know what he/she has told you? This is a key question that must be answered and will aid verification - decisions on the credibility of the information provided.

Recording and evaluating a testimony

The quality and reliability of a victim's or witness' testimony can be influenced by a range of factors, including the amount of time that has elapsed since the event, age of the witness, emotional stress, and possibly intent to deceive.

One key challenge affecting the reliability of testimony in highly politicized conflict areas is that bias can lead an interviewee to skew the information to favour one side in the conflict more than another. To the extent possible, the interviewer must be aware of the information provider's background, particularly suspected political allegiances and sympathies, and make sure to detail the case carefully. As a way to test the reliability of testimony, the interviewer should check for apparent inconsistencies throughout the interview and clarify contradictory statements.

Beyond the "who did what to whom, where, when and how" queries that are the foundation of incident documentation, the interviewer must also take care to document answers to the question of "How do you know?" When witnesses describe an event, the interviewer must check how the person knows what happened. For example:

- How was the person able to see or hear what happened? Where were they standing? Was it during the day or night?

- How did they know the alleged offender came from a particular armed group?

- How did they know the name of the offender?

- What language was spoken?

Key messages - Verification

- Ensure that all participating organizations agree and implement minimum standards of verification.

- Designated person(s) should review all information to determine it is credible.

- Cross-reference to determine credibility of information.

- Verify ages, perpetrators, etc., by asking same question in different ways to ensure information is correct

- Document precise and specific information.

- How does the witness know the information? Ask questions to ensure credibility.

Documentation

Monitoring tools

Although preferable, it is not essential that all incidents be documented in a standard format. Organizations that need information on providing a service to victims may already collect very detailed case information and it is not necessary to create extra work in duplicating reporting. What is important, however, is that an agreed minimum set of indicators are reported on.

- Determine minimum data set that will be collected in the country on each of the violations. Use of a standard format can be helpful - see Annex IX Monitoring Tools - Global Examples [1], [2] and [3] [PDFs] for samples that can be adapted for use in different contexts.

- Reports should be completed as soon as possible after the interview; greater accuracy is achieved when information is fresh in a person's mind.

- If organizations are not all using the same format, unilateral arrangements on how information will be shared will be required.

Documenting incidents

It is suggested that the minimum data provided for MRM include:

- Source of information (e.g., child, parent, witness, community leader - name not essential)

- Date incident happened;

- Location;

- Numbers of children involved;

- Nature of the violation;

- Entity responsible;

- Description and details of the incident; ensure that this is well described, as it will be key for purposes of accountability and advocacy.

- Action taken - if any;

- Child profile - age, sex, nationality, ethnicity, religion, status (e.g., refugee, displaced), care situation (e.g., unaccompanied minors, separated).

- Date of interview/monitoring report with monitor's identification when possible.

For non-personalized incidents (e.g., attack on a school or denial of humanitarian access), while it is highly preferable for child profiles to be provided, it is not mandatory for the reporting of the incident. However, where possible child profiles on each individual victim should be provided and therefore allow for greater analytical capacity and use of information.

While the above is the minimum information, the MRM also requires sufficient qualitative information or case studies to include within the reports, to illustrate and substantiate patterns of violations.

Security for documentation

- Documentation is important, but, at times, being in possession of documentation may pose risks for monitors; consider the security risks and, if necessary, complete documentation back at the office. See also Information Management.

- Security may be a concern if a staff member is in possession of a tape or involved in recording a testimony with the use of a tape; it is therefore strongly recommended that tape recording should be avoided.

- In situations that pose security risks, it is suggested that names of organization or staff are not included on hard copies nor on the information management system but that a code system is developed. See details in the Confidentiality section under Information Management.

Key messages - Documentation

- All participating organizations must agree on the indicators and the minimum data required to be documented.

- Staff should complete documentation/writing-up reports when in a safe place to do so.

- Do not include names of staff on documents.

Quality control

The credibility of MRM reports and the whole MRM mechanism relies on the quality and timeliness of information provided and recorded. While the MRM Task Force has the ultimate responsibility to endorse information contained in reports, MRM reporting coordinators are key to ensuring that information is of a high standard and that information gathering is carried out in a manner fitting with UN humanitarian principles.

The MRM reporting coordinators must ensure that for every case, appropriate standards are met and the following aspects are considered:

- Who gathered the information and provided the report? Personnel trained in the MRM?

- How were the victims interviewed?

- Was consent asked for?

- Ensure highest ethical standards, including avoidance of multiple interviewing of victims.

- Is there enough information to evidence the case?

- Is the source of information credible?

- Has documentation achieved a high level of confidentiality?

- Has security been considered for staff member, victim and witnesses?

- Has an appropriate response been offered to the child or a referral been made for service provision?

Caring for staff

Personnel carrying out a monitoring function may hear some very difficult testimonies, and it is vital that appropriate mechanisms be in place to support field staff. This can be particularly important for national staff who live in the effected communities and are unable to seek peer support due to the need for confidentiality, and for security reasons - for both them and their families.

Further reading - Monitoring

- 'Protection' An ALNAP Guide for humanitarian agencies [PDF]

- For more on interviewing children, see: 'Working with Children', Action for the Rights of the Child (ARC)

- Growing the Sheltering Tree [PDF]

- UNICEF, Reporting Guidelines to Protect at-Risk Children (though targeting media, principles related to interviewing children are useful)

39 See paragraph 2(b) of Security Council Resolution 1612 [PDF] (2005).

40 Anonymized means non-personalized information but can include child profile - age, gender, ethnicity, religion, status (internally displaced person, refugee, etc.); and details about the violation, date, location, perpetrator, etc. Appropriate qualitative detail to be included, but no names, addresses, etc. Full data to be held by the organization that collected the report. See documentation sections for more details.

41 Staff should be in a position to supply details of organizations that can provide advice and support for persons who wish to pursue legal redress.

42 See also United Nations Guidelines on Justice in matters involving child victims and witnesses of crime; ECOSOC resolution 2005/20 of 22 July 2005; and UN common approach on justice for children 2008.